By Virginia Macholl

I decided to write about Nefissa Naguib’s book Nurturing Masculinities[1] because of my academic interests in gender studies/gender roles and, on the contrary, because I do not often read about anthropology of food. The reason was also that the author has put together issues like masculinity and food, and I used to think anthropologists always write about women in relation with food. So, it was like my interests were mixed with curiosity, and it was such a good time while reading that good writing.

The author currently works as Professor of Social Anthropology at University of Oslo in Norway[2]. Her research focus on people’s relations with food and water, migration and gender. In that mentioned book she refers to well-known anthropologists and researchers that I have learnt during my academic courses, for example Lila Abu-Lughod[3], Mary Douglas[4], Fredrik Barth[5], Victor Turner[6] and philosopher Thomas Hobbes[7]. The book is based on her extensive fieldwork in Egypt and contains direct quotes of her interlocutors, which I find very helpful in understanding theory as empirically grounded.

Nurturing Masculinities starts with acknowledgment that the text is not only about the above issues – such as anthropology of food and gender – but also about memories. Reminiscences of the past are valid part of interlocutors’ stories, because they often refer to the things that were taking place somewhere in the times that are gone – and those times are recalled by them as much better than the nowadays life[8]. One of the men simply told the author: “The world was a happier place before. Here, it’s old days.”[9]. It sounds nostalgic. And in relation to food, it shows to me that some special kinds of meals can bring familiar feelings of “those better days” – they’re like a mental gateway (or a try of escape) to the days when “the world was a happier place”. And what is more, talking about food and memories (or memories about food) “opens up our discussion of masculinity in interesting ways”[10]. That can give us some information about interlocutors’ memories of childhood, their views on current relations, or on things that can be considered controversial or unwanted to tell (including gender roles). Or even secretly tells much more, just like personal duties, outgoings, inner conflicts… and so on. As the author writes, her concept of “nurturing masculinities” has been developed through exploring men’s relation to food, and it builds on the growing body of literature on “lived masculinities”[11], the concept which “unsettles the dominant trope of relying on domination and patriarchy when discussing Middle Eastern men.”[12].

As the book demonstrates, food can bring memories and open the door to much more information than we were asking for; and we can say that food gives us an opportunity to collect pleasant (or just well-remembered) memories. In the book such role of food is called the “commemorative” function of food[13]. And as we discussed during our lecture, it’s just like in a famous Marcel Proust’s book titled In Search of Lost Time[14] – where a story starts from a memory that a cupcake brings to life, in Nurturing Masculinities those groceries are bread, rice and butter[15] (in the meaning of a kind of fat, and that’s why for some richer Egyptians it can be meat too[16]).

Describing bread as the most popular element of meals in Cairo, Naguib writes in the way that reminds me of anthropology of the senses[17]. She makes a list of sensations accompanying eating bread, including smells, sounds and taste. “Eating bread is one of the most satisfying acts involving human senses”[18], she concludes. Then she quotes one of her respondents who said: “Remember, the word for bread in Egyptian Arabic is aish—life.”[19]. Another interlocutor, a bakery’s manager, told her: “Bread is like the soul to us. It’s the cheapest, most filling part of any meal.”[20]. It shows the importance of bread, and that this kind of food is more than a part of a meal. And as the author summarizes: “Bread is one of the key actors in Egyptian social, political, and economic life. Bread has a significant influence on private and public relationships, bringing about positive memories of meals and equally strong emotions about deprivation.”[21].

And the meal itself is more than just calories absorption – it’s a way of making relations. For me, it’s described like eating together was some kind of a tool (or a device) for better interaction and an excuse for gathering together and spending time, having fun and feeling well[22]. There is no important social event without food – and food is usually commonly shared on various celebrations. Food is also shared with the neighbors that are not able to make festive expenses in that time. As I understood from the text, food is an important part of social life for all Egyptians – both for those who call themselves ‘traditional’ and those who call themselves ‘modern’.

Speaking about modernity: the book shows that this word can have different meanings for different people. When Naguib takes up the subject of so-called ‘food activism’[23] in Egypt, she recalls a conversation with one of her interlocutors: when she asked if they speak English, her interlocutor replied: “Why not, it makes us modern. But remember to write down ‘Islam-based food activism.’”[24]. That fragment attracted my attention when I was reading the book for the first time; I stopped and thought to myself: hey, I have never thought about speaking in English in that way! I have never considered myself ‘modern’ just because I speak this language. Some can say it’s just a one quote, but in my opinion that small part of the text is very important/revealing for an anthropologist: it points out how people understand the world, the global processes and globalization. Having known better her respondents, Naguib observed that ‘Egyptian modernity’ relates to food too; it is reflected in sharing the food and a sentimental tie that’s between a man and his wife. Writing about one of her interlocutors, named Samir, she gives us an interesting information: “Food was both a visceral and emblematic sign of him as a modern Egyptian man. It was a medium he uses to explain his relationship.”[25]. And talking about relations – ‘food stories’ give us the pictures of Egyptian homes – but it’s about people too. Just like one of the men from the book said: “A home for me is the place where I like the food and the people.”[26].

As I have written in the first paragraph, the book also focuses on how Egyptian men find ‘being a man” and how it’s connected with food. The book suggests that we should look at the contemporary Arabic societies in a way that acknowledges their desire to live modern lives (in their own understanding of the meaning of modernity, which includes upholding of some traditional ways too). “Male behavior emerged from verbal jousting and violent acts”[27], Naguib writes. It’s a tip for the reader to not rely on stereotypes but to reach out to contemporary ethnographies.

Returning to the term “lived masculinities”, Naguib argues that masculinity is not static and thus escapes simple definitions[28]. Therefore, as she writes: “Masculine identities take many forms, and are articulated in numerous sites of cultural, social, emotional, religious, political, economic, and gendered expression.”[29], Naguib confronts the theory and the practice while referring to Matthew Gutmann[30] works: “Definitions of masculinity within anthropology — “anything that men think and do,” “anything men think and do to be men,” and “anything that women are not” — and he notes that “some men are … ‘more manly’ than other men.” Indeed, my interlocutors have said all the above.”[31]. Then she continues about the stories included in the book: “Men are shown inside the company of their immediate families, inside their parental love, and inside their intimacy, which frequently leads to self-reflection. There are no constructions of masculinity, or at least not the whole edifice.”[32]. That makes us think that everyone understands ‘being a man’ in their own way, and everyday practices are what confirms the social role that one wants to accomplish. (I mean that social roles are manifested through everyday practices, and as such they are lived and fluid too.) While ‘to accomplish’ is a good term – because like her interlocutors said, trying their best in doing what they find proper for a man is a matter of honor (men have their “honor”[33], Naguib writes), or even a duty. Ability to bring food home is considered a proper behavior instrumental in shaping the role of a family man[34]. As the respondents said too, collecting meat and bringing food home is something that makes their wives happy[35] – and making women happy is what motivates men too. “Food also connects husband and wife”[36], the anthropologist writes, implying that a relation between men, women and food exists simultaneously[37].

What I paid attention to when I was reading Nurturing Masculinities is that it includes examples of the author’s impressions she got when she was in Cairo[38]. She tells us more than about her methodology, but also about the views on the role of retelling stories in life[39]. She even quotes her own fieldnotes and I think that’s pretty uncommon in anthropological works (maybe because it gives the text emotional character that can be find unprofessional?). Anyway, for me it makes the book unconventional and makes the descriptions very vivid. I find it inspiring, and I enjoyed reading it. And it emphasizes that the anthropologist’s work is a work of interpretation – and adding ‘the proofs of the impressions”, such like those quoted fieldnotes, is for me a great idea to make the writing more individual. Individual cases are what the book is made of and the author’s point of view is just one of them And that’s what my previous post on the blog is about – see how the author’s influence on the research and text Lila Abu-Lughod has described in her writing on the cases of so-called “halfies” and feminists[40].

Bibliography:

- Naguib, Nefissa, Nurturing Masculinities. Men, Food and Family in Contemporary Egypt, University of Texas Press, Austin 2015

- <https://www.sv.uio.no/sai/english/people/aca/nefissan/> (access: 26.05.2023)

Pictures: Nefissa Naguib. https://no.linkedin.com/in/nefissa-naguib-64743063

The author of the book on an Egyptian street.

A photograph from the book titled by the author Sweet tea and described as taken in 2004.

Nurturing Masculinities, p. 75

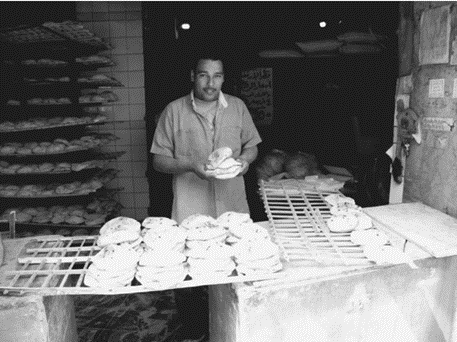

Another photograph – titled by the author A baker and taken in 2010. Here we see bread that’s called the most important part of an Egyptian meal.

Nurturing Masculinities, p. 82.

[1] Naguib, Nefissa, Nurturing Masculinities. Men, Food and Family in Contemporary Egypt, University of Texas Press, Austin 2015.

[2] See: <https://www.sv.uio.no/sai/english/people/aca/nefissan/> (access: 26.05.2023).

[3] Naguib, Nefissa, Nurturing Masculinities…, p. 4, 21, 24, see also: in the references, p. 129.

[4] Ibidem, p. 15, 27, 74, 119, 120, 127, see also: in the references, p. 131.

[5] Ibidem, pp. 18-20, p. 123, see also: in the references: p. 129.

[6] Ibidem, p. 42, see also: in the references: p. 130, 136.

[7] Ibidem, p. 36, see also: in the references: p. 132.

[8] As Naguib writes: „Among my interlocutors, the past is imagined as a time when men easily brought food home and women had all the ingredients, they needed in order to feed their men and children.”, Ibidem, p. 88.

[9] Ibidem, p. 82.

[10] Ibidem, p. 48. I think it’s a great tip for anthropologists on how to start a discussion or an interview with a respondent when we want to ask some vulnerable questions or there is a risk, we don’t get an answer when we would ask straightly about something.

[11] Ibidem, p. 3.

[12] Ibidem, p. 3.

[13] Ibidem, p. 87.

[14] First published in French in 1913–1927, in English in 1922–1931. See: Proust, Marcel, In Search of Lost Time, Modern Library, New York City 2003.

[15] See a great anthropological example of what rice and butter can mean in someone’s life: „For Mustafa Hashim, rice with samna baladi (a kind of butter – own addition) evoked his pride as a man, eating what men should eat, nostalgia, and the comfort of repeated family habits. Recipes, cooking, and meals were filled with satisfaction and captured delightful moments for him and his family.”, Naguib, Nefissa, Nurturing Masculinities. Men, Food and Family in Contemporary Egypt, p. 90-91. See also a fragment about rice on pp. 78-80.

[16] Butter occupies a unique, special place in current Egyptian culture, not because it is “butter” but because it is an accessible fat – so for wealthier Egyptians, meat is the “special fat” in the diet.

[17] She also mentions that the interlocutors told her what they feel during eating food at all – those infromation are about its texture, taste, fragrance, and appearance. See: Ibidem, p. 74.

[18] Ibidem, p. 69.

[19] Ibidem, p. 69.

[20] Ibidem, p. 82.

[21] Ibidem, p. 68.

[22] More about that food creates social relationships: Ibidem, pp. 99-104.

[23] ‘Food activism’ is taking actions by the Muslim Brotherhood, an organization of (mostly young) men that claims they don’t agree with raising prices of food, corruption, police brutality and the government’s doings that make the Egyptians’ lives worse. It’s still a religious organization, however focused on food supplies and making people’s live more „modern” (in their own understanding). Naguib writes about it: „If we take food and particular practices of everyday spirituality as contributing to people’s needs and also to the young Brothers’ identity and aspirations, then Islamic food activism may be analyzed as a practice that established connections between those receiving food and the Brothers providing food.” (Ibidem, p. 62). The author mentions that „[…] religious identity lends it a populist authenticity” (Ibidem, p. 59) and „I suggest that the Muslim Brotherhood’s food-justice activism was born of a politics of silence and exposure.” (Ibidem, p. 57).

[24] Ibidem, p. 55.

[25] Ibidem, p. 46.

[26] Ibidem, p. 44.

[27] Ibidem, p. 37.

[28] As one can read in the summary of the statements of the men that the author was talked with: „My interlocutors’ understanding of themselves as authentic Egyptian men, based on a shared consensus of values and norms, can serve as a foundation for a cultural understanding of Egyptian men.”, Ibidem, p. 97.

[29] Ibidem, p. 52. She refers here to feminist interpretations and some differences in looking at the issue of ‘being a man’. See also a fragment in the book when the author shows her personal views: „I suggest that ties of procreation are an avenue for rethinking the female-male nurturing divide in the Middle East. The concept of procreation brings men to the hearth.”, Ibidem, p. 48.

[30] He is a Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and Faculty Associate at the Population Studies and Training Center at Brown University in Providence in the United States. His works focus on gender and sexuality, reproductive health, and migration.

[31] Ibidem, p. 37.

[32] Ibidem, p. 40.

[33] Ibidem, p. 49.

[34] See an example of the family of the one of the interlocutors, Ibidem, p. 40-42. See also another instance summarized in the author’s words: „Concern about bringing home a food favorite for the children is a major theme.”, Ibidem, p. 39.

among my interlocutors.

[35] Ibidem, p. 105.

[36] Ibidem, p. 46.

[37] I dare say it can be a relation between food and people – and I understand here „people” in the meaning of husbands, wives, children, whole families, neighborhoods, and social groups (and maybe even a nation).

[38] For an instance, see her described memory that sharing meals with the people of the Middle East was the one of the nicest parts of her fieldwork: Ibidem, p. 73.

[39] „Anthropologists distinguish between life as lived, life as experienced, and a life as told.” Ibidem, p. 48.

[40] See also the original text of that author: Abu-Lughod, Lila, Writing against culture, pp. 137-162 in: Richard G. Fox (ed.), Recapturing Anthropology: Working in the Present, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe 1996.

Leave a comment